In 2019, Diamond assembled 10,000 individual genomes of nearly 800 microbial species from soil samples collected from a grassland meadow in Northern California.īut he compares this to taking a population census: It provides unparalleled information about which microbes are present in which proportions, and which functions those microbes could perform within the community. Metagenomic sequencing has advanced immensely in the past 15 years.

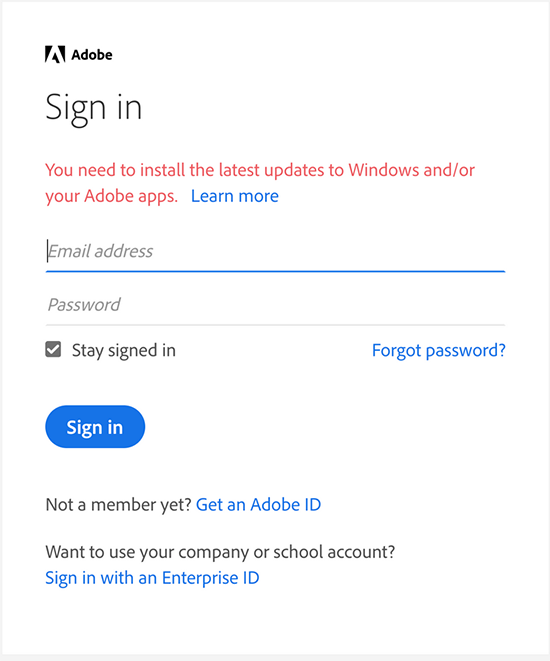

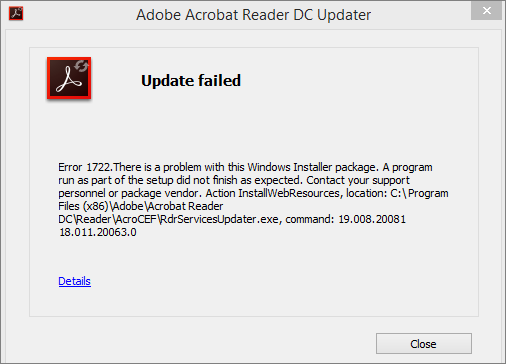

#Adobe acrobat 7.0 professional editing has no available full

6) in the journal Nature Microbiology.ĭiamond works in the laboratory of Jill Banfield, a geomicrobiologist who pioneered the field of community sequencing, or metagenomics: shotgun sequencing all the DNA in a complex community of microbes and assembling this DNA into the full genomes of all these organisms, some of which likely have never been seen before and many of which are impossible to grow in a lab dish. Rubin and Cress - both in the lab of CRISPR-Cas9 inventor Jennifer Doudna - and Spencer Diamond, a project scientist in the Innovative Genomics Institute (IGI), are co-first authors of a paper describing the technique that appeared today (Dec. "But likely, before we do that, this approach will give us a better understanding of how microbes function within a community." "Eventually, we may be able to eliminate genes that cause sickness in your gut bacteria or make plants more efficient by engineering their microbial partners," said postdoctoral fellow Brady Cress. While the ability to "shotgun" edit many types of cells or microbes at once could be useful in current industry-scale systems - bioreactors for culturing cells in bulk, for example, the more immediate application may be as a tool in understanding the structure of complex communities of bacteria, archaea and fungi, and gene flow within these diverse populations.

"This work helps bring that fundamental approach to microbial communities, which are much more representative of how these microbes live and function in nature." "Breaking and changing DNA within isolated microorganisms has been essential to understanding what that DNA does," said UC Berkeley postdoctoral fellow Benjamin Rubin.

Without a way to track the gene insertions - using a barcode, in this case - such inserted genes could end up anywhere, since microbes routinely share genes among themselves. Such tracking becomes necessary as scientists talk about genetically altering microbial populations: inserting genes into microbes in the gut to fix digestive problems, for example, or altering the microbial environment of crops to make them more resilient to pests. While this technology is still exclusively applied in lab settings, it could be used both to edit and to track edited microbes within a natural community, such as in the gut or on the roots of a plant where hundreds or thousands of different microbes congregate. Now, the University of California, Berkeley, group that invented the CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing technology nearly 10 years ago has found a way to add or modify genes within a community of many different species simultaneously, opening the door to what could be called "community editing."

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)